Ransomware has continued to play a dominant role in the 2021 threat landscape alongside the unravelling SolarWinds saga and the recent wave of ProxyLogon attacks to deploy webshells on vulnerable Microsoft Exchange Servers [1]. Since the start of the year, Cyjax analysts have tracked a malicious spam (malspam) campaign and cybercriminal operation, dubbed WizardSpider (also known as Gold Blackburn or TEMP.MixMaster). The group has had to adapt its tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) to support its attacks since the Emotet spam botnet was brought down by law enforcement in January. A successful infection and failure to detect the group’s malware and lateral movement tools can lead to the domain-wide deployment of Ryuk ransomware or its alternative, Conti.

The malspam campaign has been improved and is notably supported by several legitimate services. It uses free cloud, email marketing, and web hosting services to evade detection due to the decreased likelihood of these being pre-emptively blocked by their targets. To evade antivirus and endpoint detection and response (EDR) systems, the group uses code-signing certificates to masquerade as trusted software. Every step of the infection chain has been carefully designed to slip past basic analysis and maintain persistence.

One of the group’s tools, dubbed BazarLoader – which first appeared in April 2020 and is named for its use of the .bazar gTLD – has been the initial access for many ransomware attacks in the last six months. It is often followed by Cobalt Strike and Anchor_DNS, and subsequent network reconnaissance, lateral movement, credential dumping, privilege escalation, and eventually domain-wide ransomware deployment. [2]

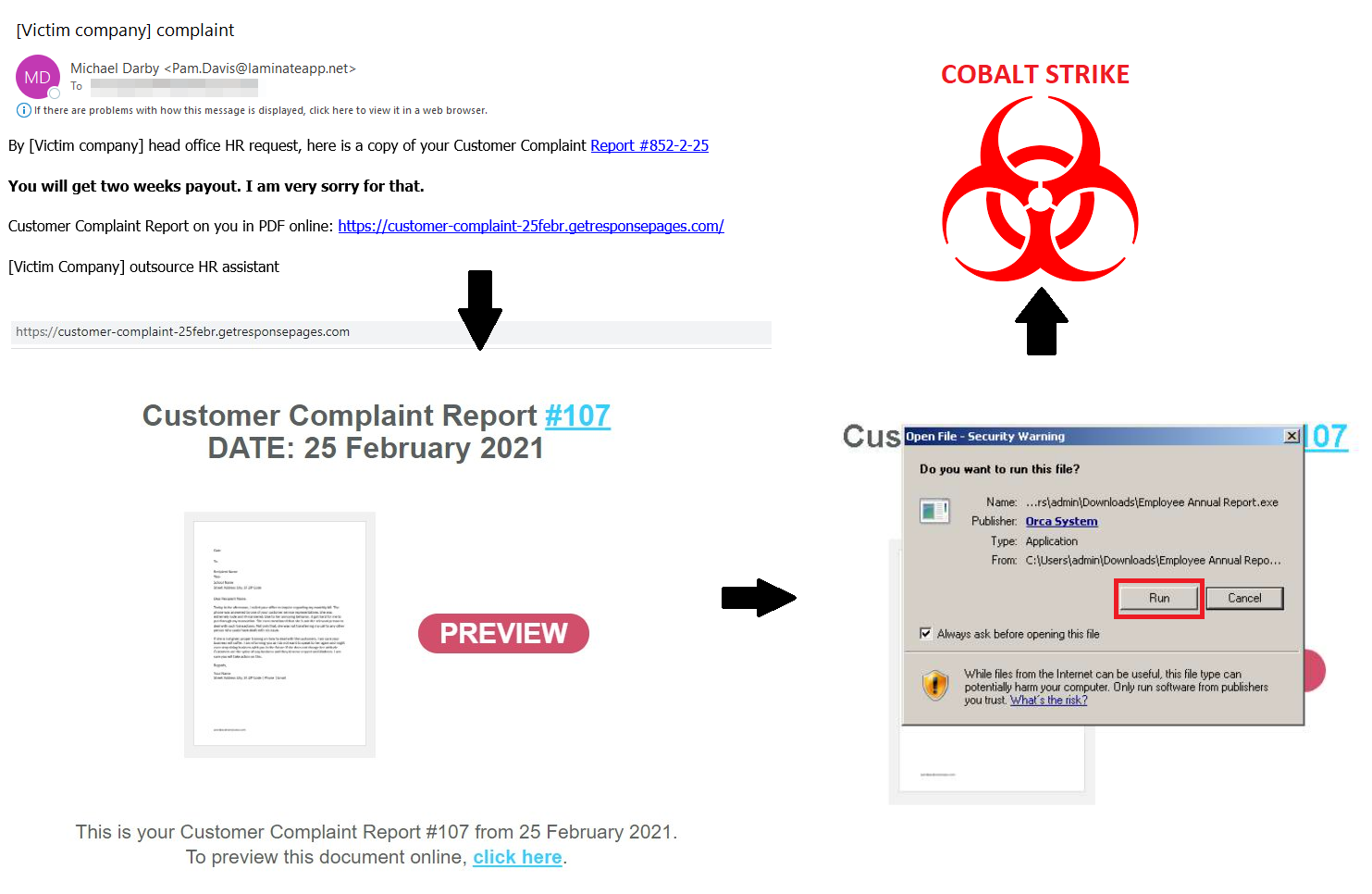

During our daily monitoring, Cyjax analysts received several reports of BazarLoader landing pages, used to serve URLs to malicious EXE files, disguised as PDFs. We dug a little deeper and uncovered several similar pages submitted to public sandboxes and reported on social media. We also found that this same chain, previously used by BazarLoader, had been replaced by Cobalt Strike Beacons. This new malspam campaign has been dubbed BazarStrike by threat researchers. [6]

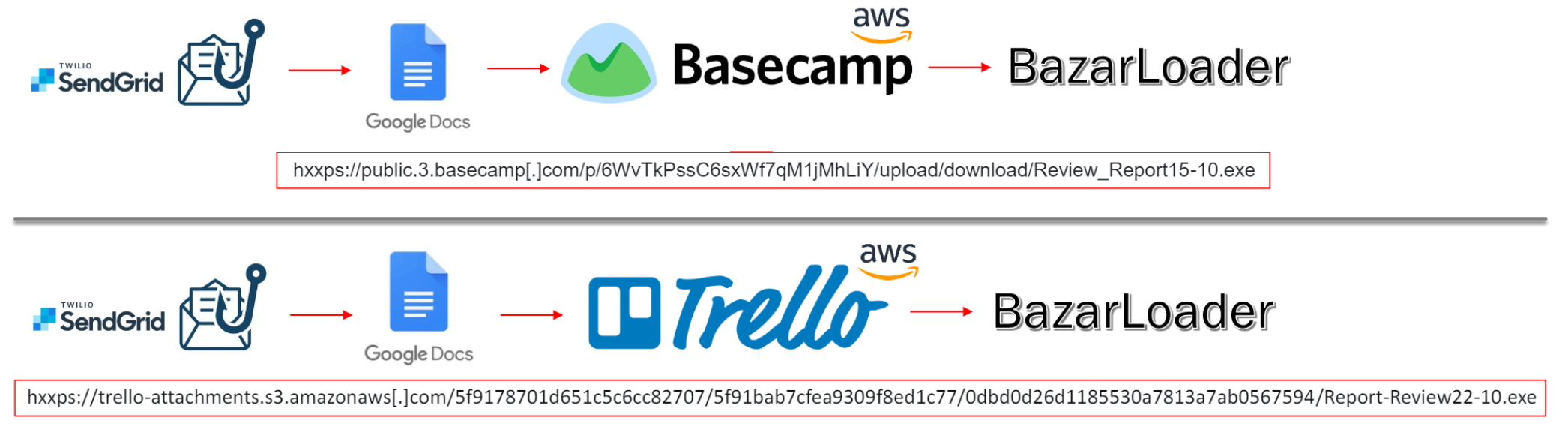

Fig. 1 – Infection chains used to distribute the BazarLoader.

Fig. 2 – Infection chain used by BazarStrike to target a UK-based online retailer.

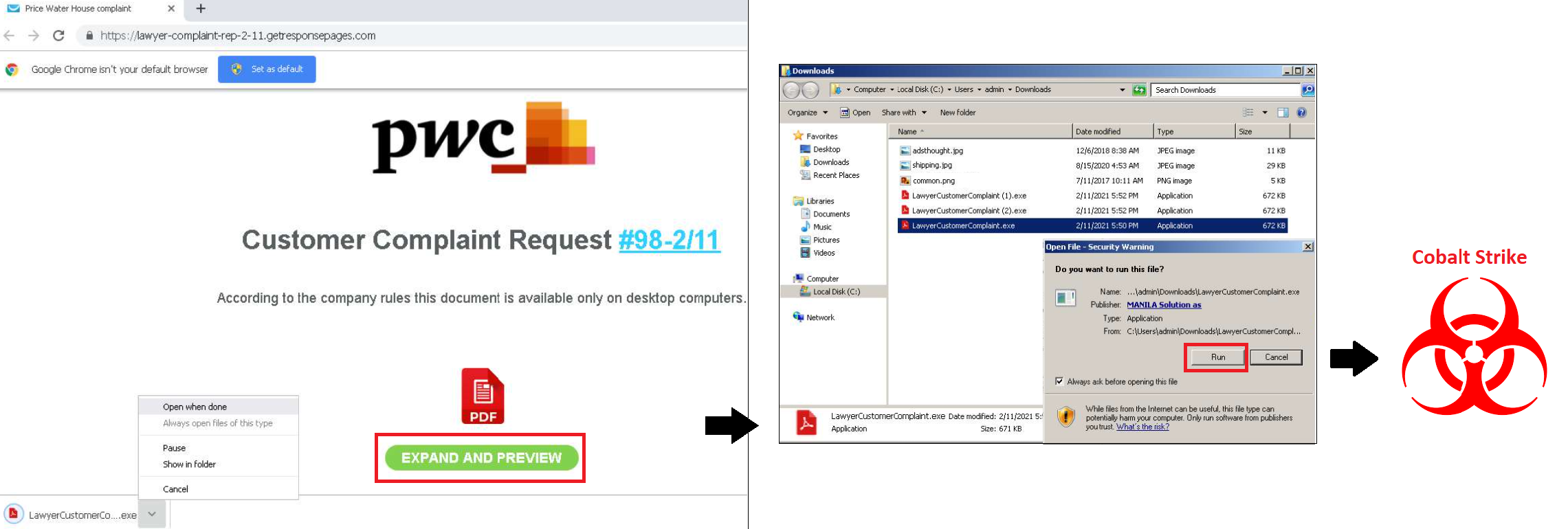

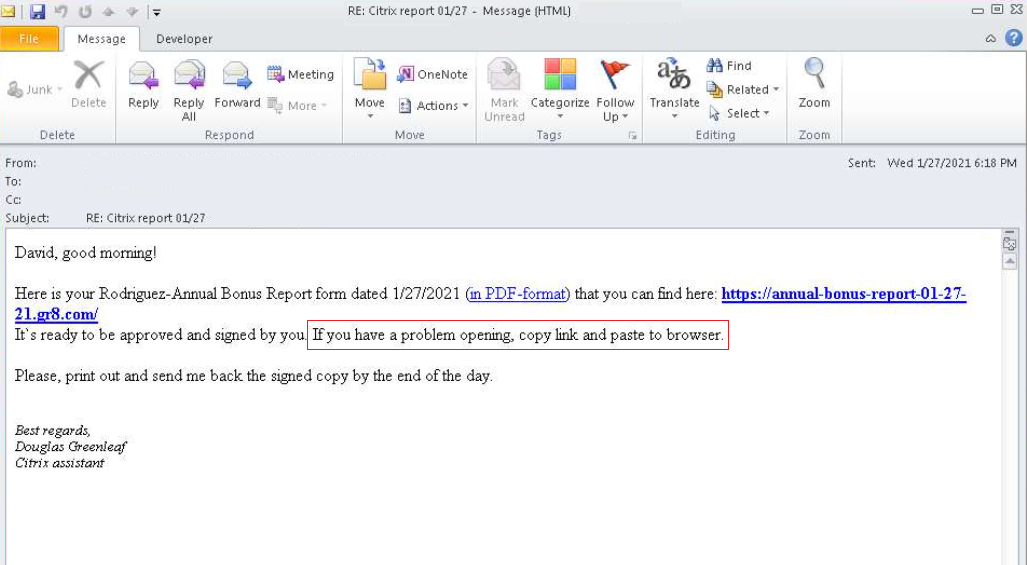

As shown above, the attackers start with a generic-looking email that contains a malicious URL to one of three marketing services: gr8[.]com, getresponsepages[.]com, and subscribemenow[.]com. The landing pages use multiple themes – including PwC, COVID-19, and medical reports – but have primarily consisted of a shared document notification.

Fig. 3 – Alternative chain using the PwC logo to distribute “LawyerCustomerComplaint.exe”.

Several months of research of malicious file and URL submission sites and open sources revealed several of the services WizardSpider uses for free payload storage. These were the following:

- Google (drive[.]google[.]com, docs[.]google[.]com) (1, 2)

- Slack (files-origin[.]slack[.]com) (1)

- Trello (trello-attachments[.]s3[.]amazonaws[.]com) (1)

- Basecamp (basecampstorage[.]blob[.]core, public[.]3[.]basecamp[.]com) (1, 2)

- SendGrid (sendgrid[.]net)

The leveraging of several legitimate platforms simultaneously makes it difficult for defenders to spot malicious activity and it is unlikely these trusted services will be pre-emptively blocked. It is also worth noting that in the spam emails recipients are also asked to “copy link and paste to browser”: this will further bypass protection systems that prevent clicking malicious links in emails.

Fig. 4 – Spam email pushing BazarStrike, masquerades as a Citrix employee.

The most recent BazarLoader campaign, dubbed BazarCall, is now making use of phone lines operated by call centres that direct users to another landing page that drops a macro-enabled Excel file. If opened, the BazarLoader is delivered. A successful infection is later followed by a Cobalt Strike Beacon and Anchor_DNS (as was the case in previous iterations of this campaign – see above). [7, 8, 9]

The WizardSpider group is one of the most successful and experienced cybercriminal gangs in operation. Its Trickbot malware first appeared in 2016 and Ryuk ransomware campaigns began in 2018. Analysis of the cryptocurrency transactions connected to the Ryuk ransomware’s known addresses revealed that its estimated earnings may be as much as $150 million. In August 2020, WizardSpider began to publish data stolen from its victims to Conti leak sites. At the time of writing, over 298 victims have appeared on those sites, the highest number of all 27 ransomware gangs that are known to use this tactic. [10]

Reducing the chances of being targeted by WizardSpider and its ransomware campaigns requires a multi-pronged approach. Clearly, the best way of preventing attacks is to stop the threat actors at the initial access stage. As such, bolstering email security to prevent phishing attacks, improving endpoint security to detect malware, and upgrading vulnerability management to prevent exploitation of public-facing applications and brute-forcing are all key defence methods. This group, however, is one of the most successful at malicious spam campaigns and ill-prepared organisations, without the right tools to detect and prevent such attacks, are at serious risk. It is recommended that organisations in all sectors look to maintain regular backups; having a recovery process in place is also key to mitigating the effects of a successful ransomware attack.